|

||

I first prepared this material

for a class at Known World Costumers Symposium in 2002, and it was an

attempt to give a "first look" at Basque clothing in period.

I will freely admit that this was a passing curiosity, an outgrowth

of my interest in Spanish costume. Although I found references to many

primary sources, I haven't yet pursued them, primarily because they

are in a variety of European languages in their Medieval or Renaissance

forms. Since I am not a linguist, I have relied on secondary sources.

(See Spanish Bibliography) Perhaps

someone with these skills will expand upon this knowledge. For early

17th century Spanish dictionaries online, I would recommend Real Academia

Española (www. RAENTLLE). |

||

As a word of caution, I will

warn that much of the relevant secondary sources are in academic language,

and translation is not for the faint of heart. I am indebted to

Marianne Perdamo, who lives in Gran Canaria for her help with complex

passages. ("No wonder you didn't understand it. It's a very convuluted sentence!! Worthy of the worse excesses of period texts.") I would also check in Vascos y Trajes. In the back there is a glossary of costume terms. Lastly, I would read on the history of the Basque people. I find that that this has done much to explain the individual nature of clothing of the region. |

||

Some

Notes About the Information |

||

General

Costume If you study the clothing of Spain, you will encounter the same basic garments seen in other European countries, especially France and Italy. For example, clothes are often made of damask, silk taffeta, velvet, linen, and wool. However, as in the rest of Spain, there is usually a "twist". In the Basque country there is an unknown (to me) fabric called "palometa" and the headwear of the women is quite distinctive. The earliest descriptions come from the Romans and Carthagenians. According to them mean wore trousers tied around the calf with strips of leather or fabric, and wore black mantles made of goatskin. Throughout Navarra mountain workers wore the skins of bears or goats. |

||

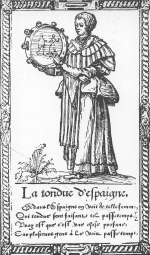

Many of the fashions seen in later years are said to have had their origins in earlier years--i.e."legend has it". For example, in certain areas 16th century women are seen with extremely short hair and sometimes with a tonsured head. "Legend has it" that this fashion dates from the Battle of Olast in 785, when women cut their hair and skirts to fight with the men. The women of Valle wear folded blue skirts, showing the red lining in remembrance of their bloodied skirts. The men wear capes of black woolen cloth and hoods with long tails sewn to simulate the tongue of the dead king that was pulled off and presented to the King of Navarra. |

||

In

the 8th Century, Ludovico

Pio (one of the sons of Charlemagne) appeared at court with other young

men dressed "in way of Vascone". Accounts say that he wore

a camisa (chemise or shirt) with wide loose

sleeves, a tunica redonda (literally a "round

tunic", whatever that is), tubrucos (pants),

a short round cape, spurs, and a lance.

XIth century mention is made of fabric stockings (early hosen?) and pleated headwear which required up to 50 yards of fabric. It is possible that these are related to those seen in other areas. |

||

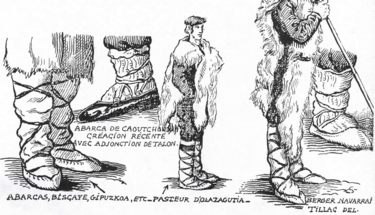

In the XIIth Century Aymeric Picaud , in the "Codex Compestellanus" tells us that Basque men dressed “like Scots”, wearing a black short cloth to their knees. He also give us an account of lavarcas- shoes of hairy leather which only covered the sole of the foot, which will be discussed in more depth later. On their heads they wore black hoods that reached to their elbows, and their bodies were covered with saias. (Saya is a somewhat generic Spanish term for gown).

|

||

Throughout the years various

styles covered the feet of the Basque people. The Codex Compestellanus

mentions "sandals" of leather tied on with wool strips There

are also mentions of crude leather held on by cords, over knitted socks.

This most certainly describes the distinctive and important regional

footwear called the abarka (ariak, lavarca).

A famous 10th Century

story illustrates the history and importance of the abarca: Towards

the end of 985 Sancho

II Garcés of Nabarra needed to lead his armies through the snowbound

Pyrnean passes to come to the aid of his brother-in-law Guillermo Sanchez,

Duke of Gascuña. The Moorish armies believed that the condition

of the passes to conquer Pamplona. But Sancho and his armies, wearing

the abarka, successfully negotiated the passes

and surprised the Moorish armies and dispersed them. In a document of

987 Sancho signs in this way: "Yo, D. sancho, Rey por la gracia

de Dios sobrenobre Abarka." |

||

|

Images from : Various Authors. (1974). Como Han Sido Y Como Son Los Vascos: Izadera ta jazdera (Caractere indumentaria) II. San Sebastian: Editorial Aunamendi, Estornes Las Hnos. Basque |

|

Another type of footwear mentioned

is exkalaproin/???zuecos. which are made of

wood and used to walk in snow and water, and are probably similar to

sabots. Also mentioned are barajones, which

are tied under abarkas to enable the wearer

to walk in the snow without sinking (snowshoes?), and borceguies,

or short boots. Lastly I have found mentioned a version of the chopine,

which are describe as being covered with painted (guilded?) leather.

In fact there was a guild of just such painters. |

||

An outer garment for men was

a hooded dalmatic (poncho) called the kapusaya (kapusayak,

capucha), and also a version opened at the sides that

had sleeves described as made of black barragán (Barracon).

Also mentioned is the capilla, a cape with a pointed hood, and a kota,

which was described as an exterior garment for rain. |

||

In the XIVth Century

men wore the jaqueta or jubon, which conformed to body without slightest

wrinkle. We have descbribed a progression of , including hosen and

braies, hosen with leather soles, and those that covered from the

waist to foot. Musicians and dancers are described as wearing the

capirote (pointed hood with small cape), saya, ropa, guarnacha, and

aljuba. |

||

The papahigo was wider “hat” covering head, ears and neck

Juglar14th c.

|

||

| In the XVth

and XVIth Centuries we are told that the women of Astorga

(Asturia) go barefoot, wear skirts that only reach to their knees, and

covered their heads and bodies with a blanket. Laliang, the chamberlain

of Felipe el Hermoso, remarked that the women of Astorga reminded him

of gypsies because of their earrings and rings. We also know that Basque

women wore pierced earrings with bells, crosses, jewelry of silver,

and paternosters of coral, jet, and amber. |

||

| Sever forms of headwear

for men are mentioned in the XVth and XVIth centuries. 1. Txano- like a beret, but larger 2. Txapela/kapela- a hat with wide brim, or short but cut in places, felted 3. Montera-Same as papahigo? |

Montera on the right? |

|

| Head Coverings

for Women (For examples of these, see the 13th

Century Gallery.) Sandoval, Chroncler of Carlos V reports that when Isabel la Catolica visited different regions, to show her love for them she wore the fashions of that town, including the hai/headwear, saya , belt, jewels. Moved on to next town, and returned the items “improved.” |

||

The distinctive headwear

of Basque women go by many names- kurbitxeta, buruko, estalkia,

oiala, zapia, tontorra (Rivadesella), curibicheta,

juicia, oyaba. Most probably the names are refer to specific

regional styles, but I frankly have made no effort to sort these out.

(This sounds like a good challenge for someone, but not for me.) No

matter the name, most of the headwear fashions are cuniform in shape,

and consist of a strip(s) of linen in some form |

||

|

|

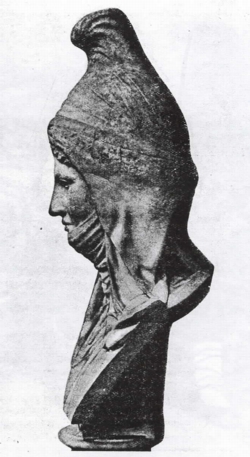

The first possible ancestor of the

cuniform headdress is a second century statue from Asia Minor which

shows an amazing resemblance to Spanish fashion in the 16th

Century. |

|

Similar Iberian headdresses

are cited by the Greek Artemidoro, and the geographer Strabo. They describe

a column a foot long, with hair tied over, covered with black wimple/toca,

like the ones in Asia Minor. This is the last evidence we have of any

kind until the XIIIth Century

when we see saints dressed in this manner. Since this predates the henin,

this would seem to make cuniform headwear not copy of French fashion,

but one that developed in Spain. |

||

| However, most of the fashions involve a long strip of fabric which

is wrapped in some way. To my mind this could also be the Basque version

of the pleated headdress seen in Castille in the |

12th/13th Century |

12th c. Sarcophagus of Doña Sancha, |

No matter what their evolution,

what women wore on their heads received much notice from writers (to

this day), based on the belief that they were a phallic symbol. My personal

opinion is that, if they ever were symbolic, that meaning had disappeared

long before the Middle Ages. From the 13th

Century there are numerous churches (such as Silos)

that have saints wearing this fashion. While saints are routinely shown

with the symbols of their martyrdom, I hardly think that it is appropriate

for saints to wear phallic symbols as a matter of course. Also, most

period travelers who described the fashion failed to comment on its

indecency. In fact, the first reference to phallic symbolism doesn't

appear until 1587, in

the writings of Frenchman Gabriel de Minut. It is only after this occaision

that the church moved to prohibit their use of cuniform headdresses

in church. In 1600 Lawyer

Felipe de Obregón, for the general Bishopric of Pamplona, imposed

fines on the husbands, and gave them twenty days to get rid of the fashion.

Failure to comply could result in excommunication and ejection from

the divine offices. Such prohibitions were imposed periodically in subsequent

years, but weren't widespread, and their enforcement seems sporadic

as well. Actually, restrictions on this fashion ARE seen much earlier, but seem to arise not from moral concerns, but from financial ones. In 1434 an Ordinance of the City of Deba (Deva) restricted their construction to no more than 30 yards of light linen, and 6 yards of heavy linen. They could not be made of gold or silk and specifically banned were embroideries of gold and silk. |

||

| How were they constructed? I WISH I KNEW. Nothing I have read tells me clearly, but we do know that they were often made of a single linen cloth strip of fabric, and that the fabric could be linen or silk in white or gold (possibly other colors) and could have gold embroidery. As for their shape, there are references to sticks (cane?) and even some to thin rods of iron. (I made mine from a Thanksgiving cornucopia, but I know that isn't right. I just couldn't figure out what do and I wanted to make one for my class!) The Museo de S. Telmo has reproductions as part of their exhibit. I haven't been able to visit this museum, nor have I gotten around to writing to anyone. (Slack, I know...) They probably have some information that I am lacking. Laurent Vita (1517) discusses how they mixed colors, so that when the neck veils were of white, then the heads were yellow, and when the heads were white, the neck veils could be yellow. |

||

|

Here's my attempt at one of these things! (I don't have any large pictures, sorry.) I used a Thanksgiving cornucopia as a base. I'm sure that they didn't do it this way, but, since I didn't know..... My site token is hanging from the peak. Someone suggested that we should hang Laurel medallions similarly on the heads of apprentices. Talk about the carrot and the donkey......! |

|

Unmarried

women with shaved heads There are pictures of women with very short hair, and even tonsures, carrying jugs and baskets on their heads. Descriptions tell us that these were unmarried women, and one possible origin has been previously mentioned. There is also the theory that the fashion originated in practices of the Gauls: Long hair was a sign of freedom, short hair a sign of slavery. It has also been suggested that the fashion began when certain areas refused to convert to Christianity. Schaschek, chronicler for León Rosmithal (1466-1467) and Antonio de Laliang (16th Century) praised the "beauty of the Basque women, who wear instead of caps a type of turban with many turns of the cloth and he maintains that the damsels/girls wear the hair shorn, [that] the unmarried women can not wear caps and married ones wear them covered in embroideries of gold and silk." |

||

|

Basque Gallery 1 |

||